The Rom Skatepark in Hornchurch has just been grade II listed by English Heritage and the DCMS.

The Rom Skatepark in Hornchurch has just been grade II listed by English Heritage and the DCMS.

The Rom was built in 1978, only a year after the opening of Skate City at the South Bank, the UK’s first commercial skatepark, but already the global skating craze had peaked. By 1980 only 20 of the 100 UK skateparks built during that brief boom were still open. Of the parks designed by Adrian Rolt and G Force, only The Rom and Solid Surf in Harrow still survive more or less intact.

The Rom from above (Googlemaps)

The Rom from above (Googlemaps)

There is a long traditon of British youth culture being imported from America and then usually mutating into something smaller and crapper (but, like all cut price knock-offs, sometimes it acquires a kind of street-urchin glamour of its own). At the Rom the sprayed concrete terrain has been formed into a series of bowls and ridges modelled on the empty swimming pools and massive drainage infrastructure of the California landscape that the Californian skaters had adopted adapted and made their own. The Rom was based on the Skateboard Heaven park in San Diego, which in turn was modelled on a drained swimming pool at an empty house known as the ‘Soul Bowl’. Skate photographer Jim Goodrich describes skating’s transition from trespass to the being a central part of any local council’s leisure spend:

Soul Bowl, located at a vacant fraternity house, was a heavily skated spot, even though it was regularly patrolled by the campus cops. It still drew skaters from everywere for quite a while. FBI pool, a unique backyard pool, got its name because the house had been seized by the FBI due to drug dealing by the owners. While we knew it was heavily watched by the cops, we skated it anyway…

Massage Pool was the longest lived and most popular spot. It was in the backyard of a house used by a massage business but in reality for prostitution. The ‘working girls’ though the skaters were cool and would often have some ‘fun’ with them after hours when business was slow.The pool eventually drew skaters from all over Southern California. It was a laid back environment where the outsiders and locals mixed easily with no attitude, a rarity at most spots.

Eventually I heard about the skate scene at La Costa. In preparation for new houses a developer had built streets and sidewalks on the hills overlooking the Pacific Ocean on the hills in Northern San Diego County. When the construction of the houses was delayed skaters were given a perfect playground on the empty street for many years. At one time or another virtually every major skater in Southern California showed up at La Costa. It had become the mecca for slalom, Freestyle and an early version of Streetstyle. it was a time of innocence and fun and became one of the largest communities of skaters anywhere in the world.

After Carlsbad skatepark was built nearby in 1976 some skaters began to drift away but La Costa remained very popular up until 1978 when skateparks emerged all over California. Skateparks created an organised skate environment, different than what we were used to – they changed the way we skated and interacted with each other in good ways and bad. Our world suddenly became much larger and the park changed our sense of freedom and close connection with the places we skated. As skating became more mainstream we began to lose the sense of adventure and pioneering spirit we had all shared. But the parks also brought more skaters together in one place, providing a stable terrain that allowed us to experiment more and to learn new tricks. New skaters entered the scene as we began to shed our outlaw image and become more acceptable in the public eye.

Jim Goodrich ‘When are you going to grow up and get a real job?’

from The Skateboarders Journal

Darren Ho, Wallos Hawaii August 1978, photo by Jim Goodrich

At the same time as the illicit rise and subsequent sanitisation of the skate scene, a landscape of pipes, drains and vacant lots was providing raw material for the artists who gathered at the now legendary Earthworks exhibition in 1968 at the Dwan gallery. It’s not only a similarity in topography that these two groups have in common but both a methodology and a mythology of trespass and appropriation. The land artists left the gallery and moved outside and not in a peaceful, going for a picnic way. They were self consciously rebels. They were punks – they were young, poor, good looking, cool, they lived in SoHo or wished they did and thus crossed over with the musicians clustered around CBGB’s. Their work was difficult, unwieldy, uncommercial and, at times brattily rebelllious. It was difficult to sell, largely because it was usually immovably huge or temporary and it didn’t look like Art. Sometimes making it called for breaking and entering and sometimes it resulted in a bust. And oddly or not, heresy or not, a lot of it looks rather like a skatepark.

Nancy Holt, Sun Tunnels, 1976 Photo: Cecilia Alemani from here

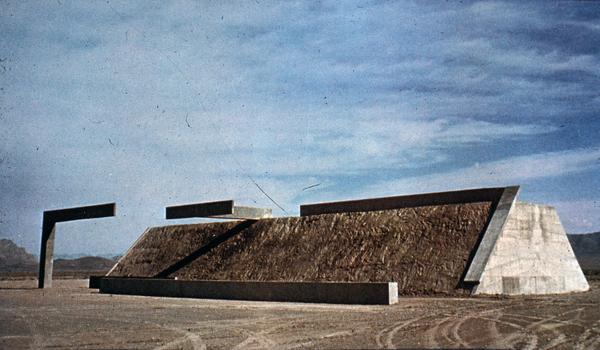

Michael Heizer City 1972-ongoing

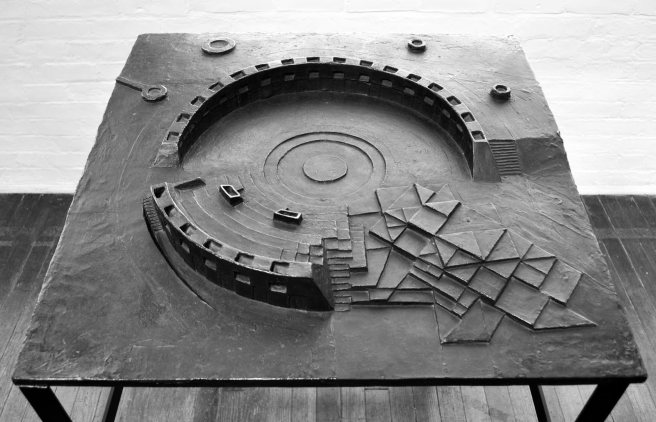

James Turrell, Roden Crater, c. 1979

So this is, what, a coincidence? A flippant connection for me to make? Just the flavour of the time? Possibly all of the above. I think there’s the germ in there for a taxonomy of rebellious architecture. But let me complete the triangle with some work that was the grandaddy of both Earthworks and skate parks: the playgrounds of Isamu Noguchi.

In the 1880s Dr Marie Zakrewska observed children in Berlin playing in sand piles that had been provided for them there. In 1885 she and the Boston Women’s Club built a ‘sand garden’ in the yard of the Children’s Mission on Permenter Street. Many of the Boston children had working parents and during the day they were left alone, so the mission provided volunteers who supervised the children’s play. It was the first purpose built children’s playground in America.

The idea of childhood was still pretty new at the time. The solidifying idea of what it means to be a child can be tracked through the 19th century via the laws introduced to limit the hours that children might work. There was a reduction to 12 hours a day in 1833. Subsequently anyone under 12 was banned from working at all, and then a compulsory state education was introduced as well as a seperate penal system for juveniles that gave them their own system of courts, prisons and, most significantly, a reduced criminal responsibility. There were many books, often mostly picture books, being written expressly for the entertainment of children, many more toys for them to play with and children’s clothes, rather than restrictive miniature adult clothes, became the norm, giving children a slight increase in physical freedom.. We had invented the idea of Play.

Ideas about play initially had a ‘biogenetic’ basis. For example: play is an instinctive mechanism that encourages physical development, or it imitates adult activity and thus prepares children for the later tasks of life. These were shortly replaced by psychoanalytical theories: play relieves childhood anxiety; it gives children a sense of control by miniaturising the world and gives them a chance to be messy and unruly without adult condemnation; it enhances a child’s self esteem by developing physical and social skills; it helps them have an understanding of themselves as discrete entities separate from other people and encourages their ability to function within social groups. In short, although they differed on the details, there was a consensus among people interested in the development of children that play was not a trivial activity but a method of learning and they soon began to find ways to guide play in order to stimulate that development and shape the future adult.

Mixed in with this were fears for the physical and moral safety of children left to amuse themselves on the street and these two trains of thought, protection and learning, are still the two ideas behind building playgrounds, though on occasion it could more usefully be expressed as protection versus learning. And there is always the question looming, who exactly are we protecting from what? In the case of the skate parks, it may well be that the main people being protected were the home owners of Southern California.

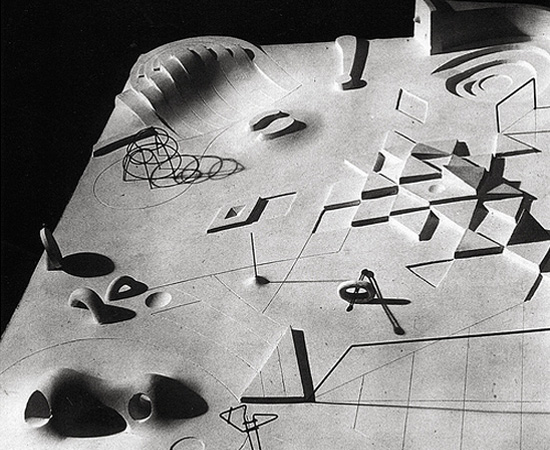

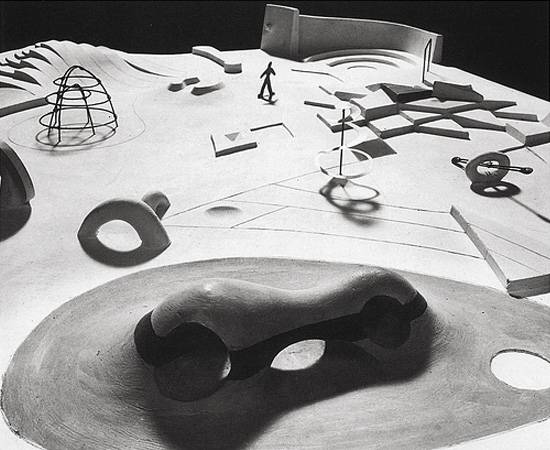

Isamu Noguchi was interested in the lived environment and what he described as ‘sculpturing space’. He’d already designed sets for Martha Graham and some of the furniture and lighting that he is best known for today when he set out on the long and quite sad journey of his playscapes that began in 1933 with Play Mountain.

‘Play Mountain was the kernel out of which have grown all my ideas relating sculpture to the earth. It is also the progenitor of playgrounds as sculptural landscapes. But these are afterthoughts. Who can foresee true significance? Not even the artist, and he is the least able to convince. With the help of Murdock Pemberton who was then art critic on the New Yorker, I took a model to show Robert Moses, the New York City Parks Commissioner. We were met with thorough sarcasm.’

In spite of this reception, Noguchi continued designing playgrounds. He designed many, very many playgrounds and yet somehow, through a mixture of bad luck, bureaucratic inefficiency and direct opposition – and in particular something that seems to amount almost to a vendetta by Robert Moses – none were built until Kodomo No Kudi near Tokyo in 1966.

Noguchi tried to get a playground built in New York every decade of his life. He was actually commissioned to do one at the UN Headquarters in 1952. A private subscription was raised, and it seemed a perfect match. The UN were looking for a new and more imaginative playground for the small children of the delegates and the local neighbourhood that would match the spirit of idealism and goodwill engendered by the United Nations:

“and everybody was enthusiastic about it including the people at the UN and, of course, myself… . The playground was killed by ukase from a municipal official who is supposed to run the parks in New York, and who somehow is the city’s self-appointed guardian against any art forms except banker’s special neo-Georgian… . Eventually the United Nations had to submit to Moses, who I understand, threatened not to install the guard rail facing the East River.”

He was commissioned to design a playground at Riverside Drive, a project that went through many set backs and iterations from 1961 to 1966. Noguchi worked on this with Louis Kahn in the hope that Kahn’s clout might see the project through. Kahn was an ideal collaborator: “Each time there would be some objection and Louis Kahn would then always say “Wonderful! They don’t want it. Now we can start all over again. We can make something better!”

The plan was finally accepted, Mayor Wagner had signed off on the project – but then John V Lindsay defeated Mayor Wagner on a fiscal responsibility ticket and Riverside Park playground was an early casulty.

Noguchi completed gardens and monuments, but the only playgrounds built during his lifetime were Kodomo no Kudi and the playground in Piedmont Park Atlanta, a comission in 1975 that had not only money but political clout to push it through. And of course, there was no Robert Moses in Atlanta (there is, surely an opera to be written about this? We have the sets already.)

Piedmont Park Alabama from here

Piedmont Park Alabama from here

So what we are left with instead of the parks is a lifetimes worth of models and an idea thirty years ahead of its time. It is hardly plausible that the monumental earthworks of Noguchi, both the unbuilt playgrounds and the completed gardens and sculptures, did not have some impact on the Earthworks artists. And, though unbuilt, Noguchi’s playgrounds, with their enourmous respect for the sensibility and creativity of the child, are an essential part of the the evolution of childrens playgrounds and the sizeable academic discourse on Play. But did the designers of Skateboard Heaven or the designers of The Rom have some inkling of Noguchi’s milestone work in playground design? More than that, might they have been poring over Artforum, at the same time as they were looking at Skateboard magazine? Could that explain the existence of this piece of Romford Noguchi?